The Hermaphrodite Brig Whaleship Daisy

Daisy

was built in 1872 by Nehemiah Hand and Son in Setauket Harbor,

Long Island, New York, for William Swan and Sons (later John Swan and Son)

of New York City for the Caribbean fruit trade. She was a profitable

merchant ship and known for her speed.

In 1907, Daisy was purchased by a consortium of investors

in New Bedford, headed by Captain Benjamin Cleveland, for

conversion to a whaling ship.

During the conversion, Daisy kept her original rig,

a hermaphrodite brig, but the crew quarters were enlarged

and the various equipment used in whaling added. She carried

davits for five whaleboats and wisker-booms at the stern for

a spare whaleboat. Her crew increased from perhaps 8 to 10 men

to 34 to 38 men.

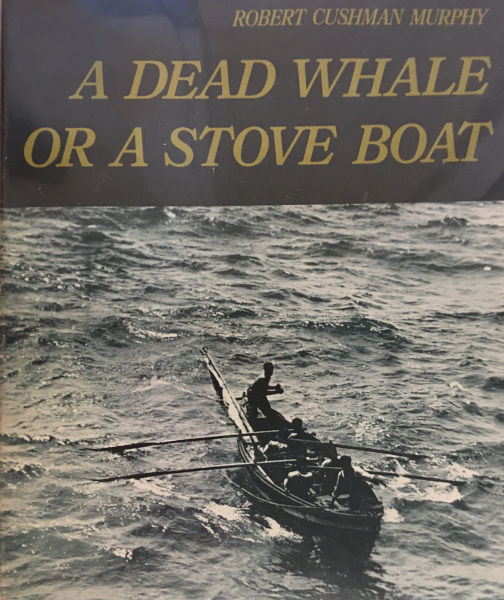

To my knowledge, there are no existing plans for Daisy as a whale ship,

although her appearance is partially documented in photographs taken

during a 1912-13 voyage to South Georgia Island by Robert Cushman Murphy,

who sailed aboard her to document the marine and island birds of the

Antarctic on behalf of the American Natural History Museum.

It was Murphy's documentation of that voyage and of life aboard an

American whaler in the last days of the industry that interested me

in Daisy.

The slide presentation below gives some additional information on the

development of plans for Daisy as well as more information on the ship,

Murphy,

and Captain Benjamin Cleveland.

It also shows construction of the model.

If interested in the background for the model and how it was constructed,

please scroll through the slides.

If you wish a copy of the full set of plans, the detail drawings of furniture, equipment, rigging and so forth, and the builders' notebook, these are available as a set from Taubman Plans, now a part of the Loyalhanna Boatyard. Most of the available plans are on-line, but for Daisy plans, you will need to email them directly to ask about availability and price.

Slide presentation on building the Daisy whale ship model

Whale Hunting and Harvesting on the Daisy

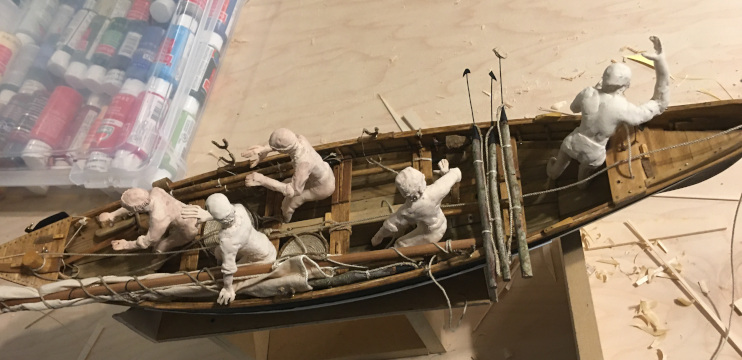

The following photos are of the completed model/diorama. One goal of building the model as a diorama was, in part, to document the processes involved in the whale hunt. In simplest terms, the work of producing whale oil, after arriving on the hunting grounds and before sailing home, happened in three stages.

Whale hunting was the first stage, during which whales were located and killed by the crews of the whale boats, 6 men each in four whaleboats, in Daisy's case leaving 10 men aboard for ship-handling. If five boats were deployed, the total crew was larger - up to 38 men - to crew the five boats and leave eight on the mother ship to crew her. During the 1912-13 voyage, when Murphy was carried, one set of whaleboat davits carried Murphy's little dory, which he used to explore islands or on the open water when documenting the marine and shore birds on the trip. The diorama is of that voyage, so Murphy's dory (and Murphy) are included.

If the hunt was successful, the dead whales were towed back from the killing field and brought alongside the whale ship by the whaleboats and were secured by chains to the larger ship for before starting the second stage.

Cutting in was the second stage, when one whale at a time was brought along the starboard side of the whale ship and secured by a chain around its tail, just forward of the flukes. The chain passed through metal lined hawse pipes onto the main deck, just aft of the break of the forecastle, and secured to large bitts forward of the foremast. This allowed the whale carcass to rotate or spin as it was stripped of its blubber layer by removing it in a continuous spiral strip. Removing the blubber is described in more detail below.

The third stage was called trying out

and was the cooking or boiling of

blubber pieces to release the oil in them. The oil was then cooled in

tanks on deck and later transferred to large wooden casks stowed below

for the return voyage.

These three stages generally occurred on different, subsequent, days. Sometimes a day or so elapsed between on step and the next, and sometimes one stage took several days, as when there were many whales to process. Daisy, in her career, processed as many as seven whales at one time. While awaiting the cuttting in, the additional whales to be processed were towed along the port side, chained together in a line. Under these circumstances, they made a feast for the many sharks that accompanied the ship and the sea around the vessel became a roiling bloody mess.

I modeled the Daisy during cutting in as a diorama, and built the model in 1:64 scale. I had just finished a separate diorama of the whale hunt incorporating a model of a Daisy whaleboat in 1:16 scale from the Eric Ronnberg Model Shipways kit and it had been a great source of additional information about the boats and equipment used in the hunt. The diorama showed the harpooning of a sperm whale, actually the placing of a second, back up harpoon, into the whale before the crew frantically rowed to a safe distance. Photos of that model are here.

Following is a discription on how the cutting in

was done

on an American whale ship of that era.

American whaling practices did not change much during

the time that the industry operated in this country. By the time of

the Daisy's 1912 voyage, other nations had moved ahead adopting more

modern methods of hunting, killing, and processing whales, including

on-shore processing of whales hunted and killed by specialized, faster,

small ships using harpoon guns and explosive harpoons.

But not the Americans.

A whale ship had several special features peculiar to the work of the vessel. On the starboard side, in the waist, a whale ship had a special removable section of bulwark which gave access to a cutting staging. The cutting stage was fastened with hinges to the side of the vessel and lowered to just above the waterline so the men standing on the stage were just above the carcass of the whale to be harvested. Whale ships also has additional hawse holes through which passed the chains securing whales aong side. Some ships had two hawse holes forward and one aft on the starboard side and some had additional hawse holes on the port side to secure additional whales awaiting cutting in. Photos of the Daisy show only hawse holes forward on the starboard side. For the cutting in, the whale carcass was chained by the tail flukes and positioned so that the head of the animal was just below the cutting stage.

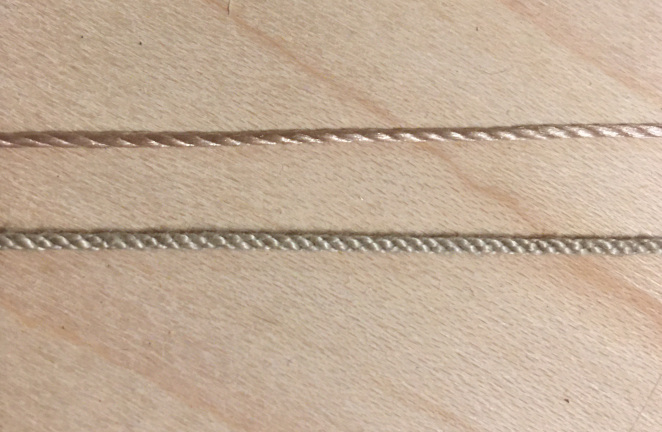

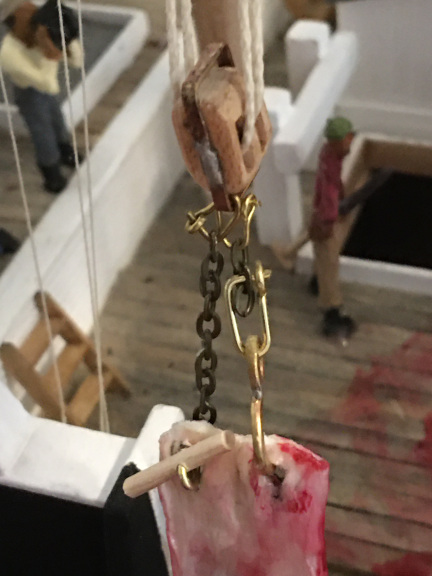

The crew on the stage first used sharp spades to cut through the whale skin and blubber layer, down to the muscle layer. Then they cut one or two holes in the blubber and skin and fastened hooks and toggles on chains through the holes and passed the chains up to a massive, specialized tackle which hung on a huge and long pendant from the top of the main mast, at the doubling. The falls from the blubber tackles (there were two) passed through large blocks on port and starboard side near the foremast to each side of the windlass at the forecastle. Crew working the windlass used the tackle to raise the blubber up as the crew on the stage used their spades to cut it free.

The blubber hook and toggle inserted into the blubber being stripped away from the whale.

Once the tackle had reached the limits of its travel upwards, an officer

used a boarding knife

to cut two new holes in the strip of blubber

so the crew could secure the second tackle's blubber hook and toggle to it.

Then the office used the boarding knife to slice the blubber strip

free, just above the new tackle location.

The blubber strip, weighing thousands of pounds, swung free and was lowered

to the deck by the first tackle (starboard windlass) while the second tackle

(port windlass) resumed the removal of the blubber from the whale's body.

Pictures below show the massive blocks of the cutting tackle and the hauling end of the tackle passing to each side of the foremast through large viol blocks to the separate sides of the windlass. This arrangement allowed each of the two cutting tackles with the attached chains, hooks, and toggles, to be operated independently as described above.

These huge pieces of blubber were called blanket pieces

and

once on deck the crew used spades to

cut a blanket piece into smaller pieces for stowing below deck

in the blubber parlor

of the main hold.

When the carcass was flensed completely and all blubber removed, the

head of the whale was removed. In the case of right

whales, the whale

bone or baleen was removed and cleaned and transported back to port

with the oil. Whale bone corset stays were, for example, made from

the fine bones of the baleen (filter) the whales used to feed.

In the case of sperm whales, the jaw was removed to recover the teeth,

also in demand for such things as scrimshaw or other uses for the ivory.

In addition, the entire head of the sperm whale was harvested.

The crew cut away the upper forward part of the head to get to the

spermaceti, a waxy substance encased deep in the head, which yielded

a particularly high quality oil and was processed separately from the

blubber. This oil, for example, was used in watches. If the dead

sperm whale was a small one, the head was brought on board with the

blubber tackle and harvested there. If the whale was large, the head

would be harvested by men working on the stage as the head was

too heavy to bring aboard. The head of a sperm whale was about

one third the total length its body.

Once the blubber and head had been harvested, the carcass of the whale was simply unfastened and allowed to drift free, food for the sharks and scavengers of the deep.

Later, usually the next day,

after all the blubber was on board and the try works set up

the boiling began. Blubber on deck or retrieved from the

blubber parlor was further cut up into pieces

1 – 2 feet square. These pieces were then sliced part way through,

leaving skin intact, by crew using special knives, working

on makeshift tables set up on barrels. This cutting

of the blubber into thin slices exposed more of it and

facilitated the cooking out of the oil in the blubber. These

pieces were called bibles

for their

resemblance to a large, open book with many pages.

The bibles then went into the large iron cauldrons over

the fireboxes and boiled free of their oil.

When the bibles had given up their oil, they were fished

out of the oil and set aside to be used as fuel for the

fireboxes heating the cauldrons. This burning of the

spent bible pieces generated the dense black smoke for

which whalers were known and by which they were recognized.

There is a scene in the movie Master and Commander

in

which the HMS Surprise lures the French raider to her by

masquerading as a whaler, attracting the enemy ship by

generating dense black smoke as if trying out a whale.

Crews generally rigged a smoke sail

over the chimneys

of the tryworks to deflect the greasy black smoke from

the ships sails and other equipment.

Plenty more information about the processing of whales can be found in the sources cited in the presentation.

Here are the pictures of the Daisy diorama:

The model is about 33 inches long overall, with the

hull being 22 inches long, 6 inches wide, and about 33

inches tall, from the surface of the water

to

the top of the main mast.

On the starboard side the cutting stage is shown lowered, the bulwark section removed, and the cutting tackle is pulling up the third piece of blubber being removed from a small (fifty feet long) sperm whale alongside the vessel. You can see the men on the stage using their spades to help free the blubber strip being hoisted up by the tackle.

On the deck, other crew men are cutting the large piece of blubber into smaller pieces that can be handled easier and sliding the smaller pieces into the main hatch.

Another photo, from the port side, showing crew, in the waist of the ship using spades to cut up the previous blanket piece. on deck into pieces small enough to be man-handled Others are uing blubber forks to slide the smaller pieces through the main hatch to the blubber parlor where several other men are cutting it further and stowing it until it is time to try it out. The deck at this stage was a slippery, oily, wet and bloody mess.

At the same time, the cooper is busy on the quarterdeck sharpening more spades, several crewmen are finishing up unloading the equipment from the whaleboats, just returned from the hunt, and stowed on their davits. The first picture below shows an overview of the quarterdeck. The wheel is lashed. The whaleboats are on their davits and being emptied of equipment. Whaleboats were remarkably sturdy for being so lightly constructed as they were placed into and hauled out of the water with the crew and all equipment aboard.

In the first picture also, the cooper and his assistant

are sharpening spades. The lid of the spade box

had been removed and stowed temporarily on the cabin roof.

The spade box was mounted on deck

on the starboard side of the quarterdeck and stored many

cutting spades with handles of differing length depending

on how they were to be used. The length varied from about

five feet to nearly twenty feet. The shorter lengths were

used on the whaleboats and for cutting blubber on deck and

the longer lengths used on the cutting stage.

Murphy is also on the quarterdeck, taking pictures with his Graflex camera. His dory is stowed on the forward starboard whaleboat davits, just forward the cutting stage.

The last two pictures in this group show a whale boat and its equipment and a shot of the boat equipment being unloaded and placed atop the cabin roof. Ready for the next hunt. For the model, I made five whaleboats with full sets of equipment. Four were mounted on the davits and one spare on the whisker booms.

While on the t'gallant forecastle, other crew are working the rocker to drive the windlass, and others are holding tension on the hauling end, starboard, as the blubber rises. Blubber is a very complex structure, and very tough. It is not the simple layer of fat in popular understanding, but dense connective and vascular tissue with tendons and ligaments and is securely attached to the deeper musculature layer. The fatty tissue is encapsulated by the connective tissue. A whale ship needed to be careful when pulling free the blubber, as it would be possible to exert so much force trying to tear away the blubber that it was possible to drive the base of the main mast through the keel or to otherwise damage the hull by springing open the seams of the planking without the blubber tearing or giving way. Blubber is that strong.